Lovely Little Game Interactions

Alan Wake II is an amazing video game. A sequel to Remedy Entertainment's 2010 sleeper hit and coming off the back of the award-winning Control, it showcases how Remedy are masters in creating modern gaming experiences. A compelling story set in an intricate universe, with tight controls, and a level of fidelity that is almost unparalleled in the industry. The game features stunning graphical effects, elaborately detailed locations, many hours worth of voice acting, and character models that move in ways that further blur the line between the virtual and the real.

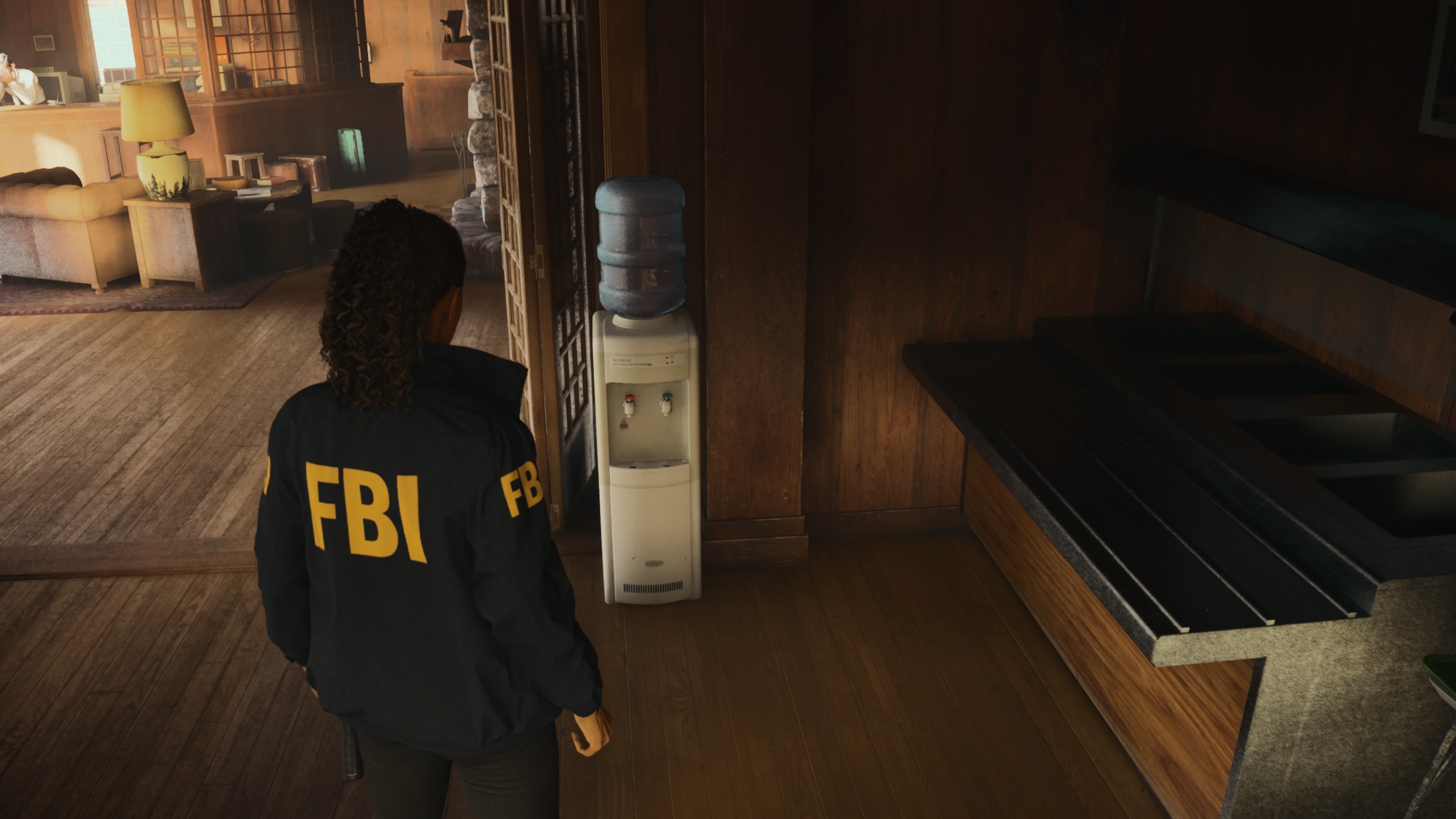

What it doesn't feature is a water cooler that makes a gurgling sound when you interact with it.

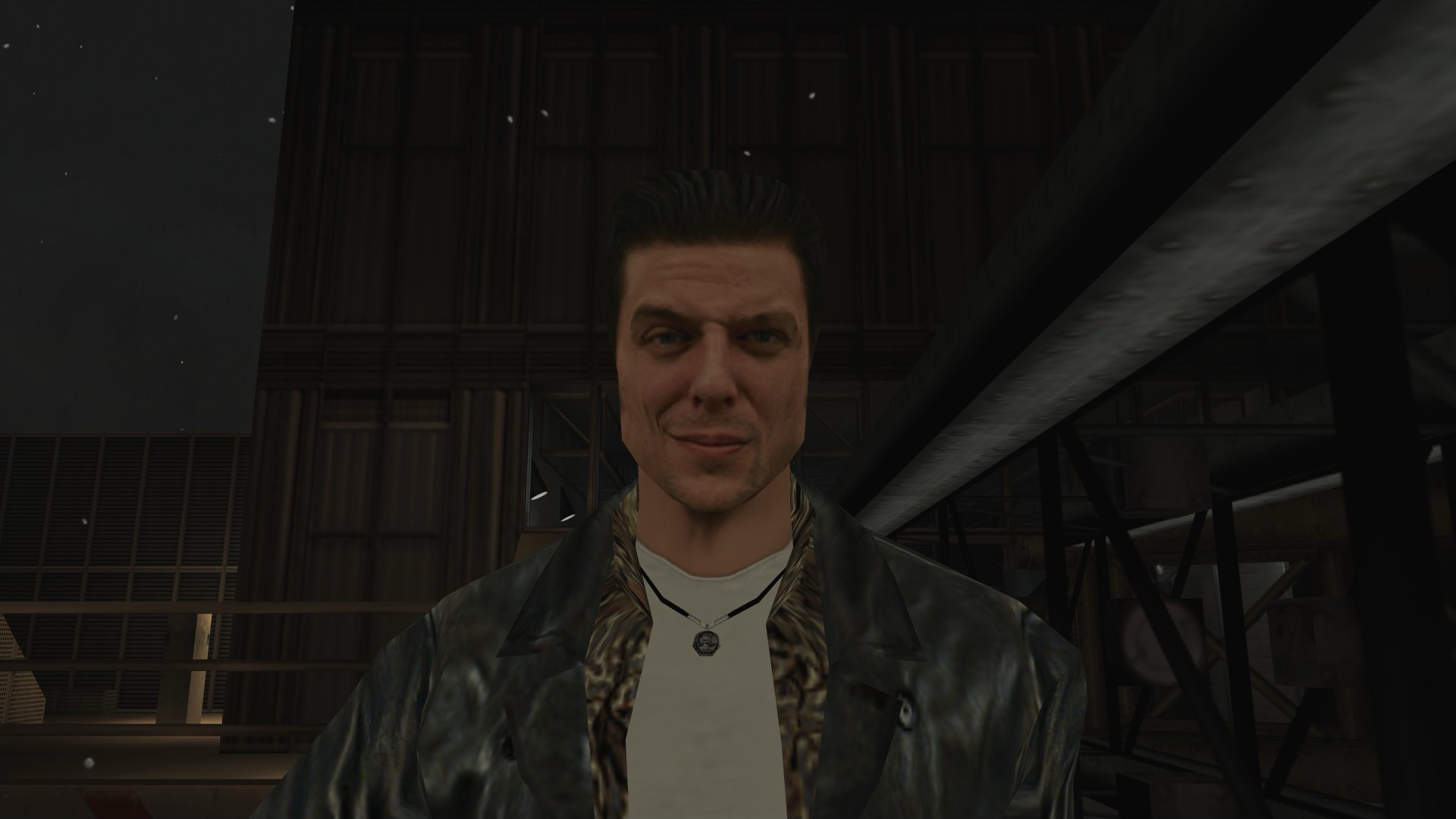

Max Payne is an amazing video game. Released by Remedy Entertainment in 2001, it had groundbreaking John Woo-inspired gunplay and an atmosphere and storyline which in hindsight is a clear progenitor of Remedy's unique storytelling style. It may not bring your neon-light-clad gaming rig to its knees, but it has a definite vibe and used all the clever techniques in the books to compensate for its lack of polygons.

Max Payne arrived at a time when developers had been pushing hard against the limits of what was possible with 3D graphics. Half a decade had passed since Quake and 3D rendering was both well-understood and constantly evolving. Max Payne was a good looking game for the time and Remedy did a great job in making the world feel believable and memorable. Not to mention blessing us with that iconic facial expression.

Computers at the time didn't have the power to render mountains of objects, so developers would create sparsely decorated corridors where the few available items had to carry a lot weight in making the world feel more real. A few boxes and a bookcase; a television and a toilet; it all helped to set the scene and immerse you in the universe, and it was even better if you could interact with them. Having the game world respond to you outside of the main gameplay loop really helped pull you in. TVs could be switched off, drawers could be pulled out, and you would find bespoke animations in lots of random places. It made you feel like you could take a break from gunning down mafiosos to just sit on the couch if you really wanted to.

One aspect of this limited interaction that I genuinely miss was that nothing was advertised. You had a use button which was used to open doors and cabinets, and it was up to you to try to press it when in front of these random objects. Often they wouldn't do anything, but every time I encountered a small, superfluous reaction it felt like the game world was more alive. That behind the locked doors and outside the permanently-shut windows there was a million similar objects waiting for me to use them.

This wouldn't be possible in modern video games, of course. The high level of detail in the environments means that your character is at all times surrounded by a hundred different objects which could potentially react to a curious pressing of the use key. It would be a frustrating and exhausting experience of walking into a room and not know which of the available cabinets or drawers or chests could be opened. Games have solved this by just telling you which objects can be interacted with, usually by providing an indicator which changes to the appropriate button as you get close.

This is great in terms of improving the gameplay experience, but it has the negative effect of deadening the world around you. When I enter a space I am very aware of what is interactive and what is just set dressing; the polygonal equivalents of paint on the wall. I genuinely believe there is something lost when I am no longer responsible for testing the limits of the interactivity. In the same way that nothing told me I could make the water cooler gurgle or leak, nothing told me that the lockers I passed by earlier could be opened to reveal ammunition or health items. Having to find the interactions myself and being rewarded by a playful animation or more resources feels incredibly rewarding.

But as rewarding as it may be, and as wistful and nostalgic as the experience of playing Max Payne again made me feel, I wouldn't want to go back. I can't imagine any other way to navigate the dense environments of modern games without some indicator as to what will respond to my prodding and what will sit there in mocking silence. As much as I don't feel immersed when I'm just scanning an environment for interaction indicators, the alternative would be to either remove most decoration so that I have fewer options, or force me to interact with everything, being disappointed most of the time. We can't have it both ways, and if we want the stunningly detailed worlds of modern video games we must accept that most things are just there to be looked at.

Oh, and in case you're curious: Alan Wake II does have a water cooler in it, but it gurgles by itself and will never know you were even there.