raylib vs. Godot: A Highly Subjective Comparison

So I want to make a game.

I got into coding because I wanted to make games, a motivation that's not uncommon among my programming peers. I may never have gotten a job in the games industry, but I have often dabbled in game development over the years, from contributing to LÖVE to taking a master's degree in Computer Games Technology. The dream of my younger self to have a career in games may be dead, but the itch to create lives on!

The indie game development scene has changed a lot since I first wrote a line of code and cemented my future career as a Certified Computer Person™. Several years ago, back when Unity was growing in popularity, I remember remarking to a friend that the era of frameworks like LÖVE was over. If someone came to me asking how to get into game development I wouldn't hesitate to point them towards Unity. That conversation was about a decade ago and despite Unity having completely consumed the indie game development space, it hasn't exactly spelled the death of simpler libraries and frameworks. I've also found that my opinion on the matter has been thoroughly changed. If I was asked the same question about "where to begin" now it would be harder to answer, not just for a beginner but also for myself.

The year is 2024, I've been programming for over two decades, and I want to do some game development. Where do I begin?

Finding the Fun

I can suffer from choice paralysis when it comes to the tools I use. Programming is such a wide field with seemingly endless options so I face the question of where to begin with absolute bewilderment, if not outright dread. I can't remember how many editors I've tried or libraries I've played with, and in my folder of unfinished side-projects I count eight different programming languages. With a field of unrealised ideas laying in my wake like discarded toys I am loathe to begin yet another project whose future is equally uncertain.

What I'm trying to discover with this article is to find the fun. I genuinely enjoy programming and I am itching to have a project to dig my teeth into. Something challenging, with a bit of purpose behind it, but also without any deadline or expectation other than existing for its own sake. I want to make a game because making games is fun. It's just difficult to push myself over the threshold of inactivity without that disconcerting voice in the back of my head telling me that I'm making all the wrong choices. Any choice of engine will come with caveats and compromises, and I worry that once things get difficult I will have wandering eyes seeking seemingly greener pastures. It's frustrating how this doubt does little but distract me from the act of working on the game itself.

So, rather than sit here and watch the ashes of my ambition be scattered to the winds of time I'm going to try something radical. Well, perhaps not radical, but at least I'm going to do something about this incessant indecisiveness. I'm going to build a small proof-of-concept game demo in several two different game engines and figure out which one I like best.

As the title of this article has given away, I will be testing: Godot and raylib. My decision was based mostly of the vibe I had been getting from the two projects and their place in the discourse surrounding indie games development. They both purport to be the cool alternative to the big guys, and as a bit of a cool guy myself I definitely don't want to be caught using something mainstream.

Philosophical Differences

Another important aspect of why I chose the options that I did was how dramatically different they were. Godot is a complete engine with its own editor and scripting language whereas raylib is a small-ish library that provides you with a bunch of utility functions and then leaves the rest up to you. Although it may seem like going for the fully-featured engine is the more sensible choice, I've had a hard time making a decision because I don't know if I'll actually enjoy working in an environment.

I'm one of those "traditional" sort of game developers who got their start building games around a main game loop. My experiences with editor-based engines have always felt somewhat discomforting compared to the simplicity of the loop, even with separating things like physics and graphics into their own threads.

while (true) {

// Process input

readKeyboardState();

readMouseState();

// Update game state

float dt = timeSinceLastLoop();

for (Entity *entity : entities) {

entity->update(dt);

}

// Render

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

// ...

glFlush();

}

This way of building games has never gone away, despite what I perceived as a tidal shift all those years ago, and is probably what drives the bigger game engines under the surface. There is even a thriving community that has sprung up around championing the idea that it's more fun to build games unfettered from the weight of a game engine. The indie games industry may all have gravitated towards Unity and Unreal, but the weirdos doing weird stuff are sticking to the main loop; as god intended.

Seeing as my first introductions into game dev was using this technique, I find it familiar and welcoming. Whether I will actually enjoy it in the long run is another matter, but figuring that out is the entire point of this whole endeavour. I may be overly romanticising the die-hard DIY approach, but I can also imagine that spending my time fiddling with a model culling algorithm is going to be more rewarding than trying to accomplish the same effect using an editor's GUI menus.

The Game

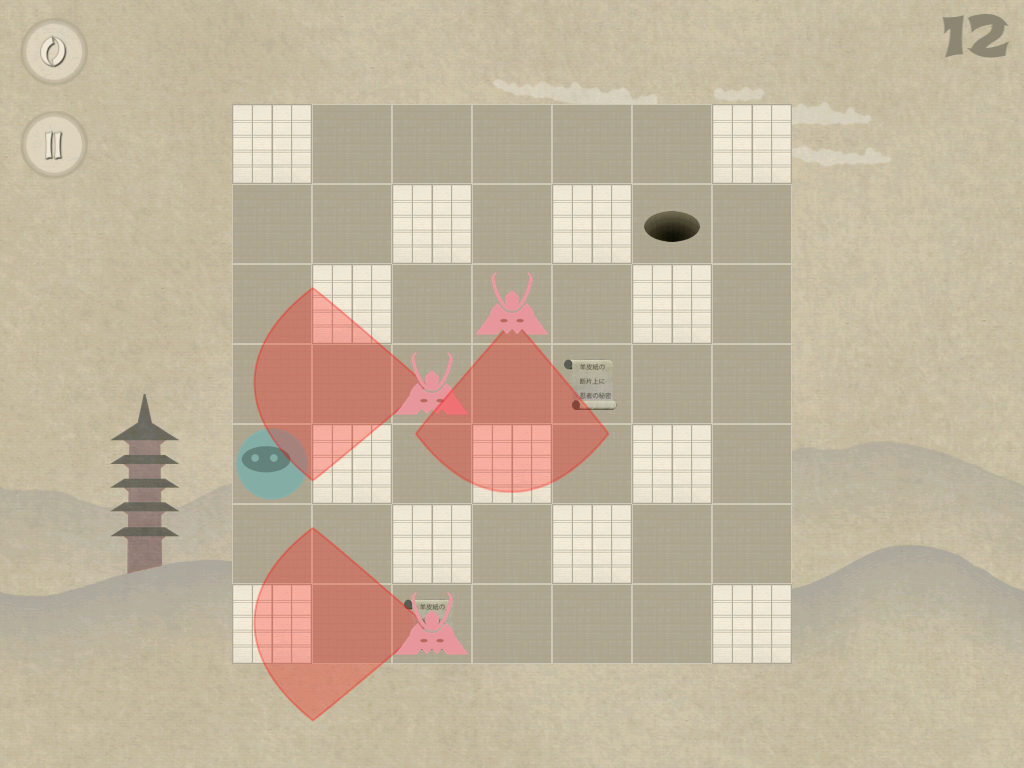

To have any chance of comparing anything I need a project to work on, so here I introduce my incredibly ambitious dream project that has no hope of ever being completed:

I want to make a 3D point-and-click adventure game!

Why? Well, I genuinely love point-and-click adventure games. The genre—despite being considered dead for decades—is thriving with a constant stream of indie releases, and I am happy that we live in a world where niche game genres can survive with the support of their true fans.

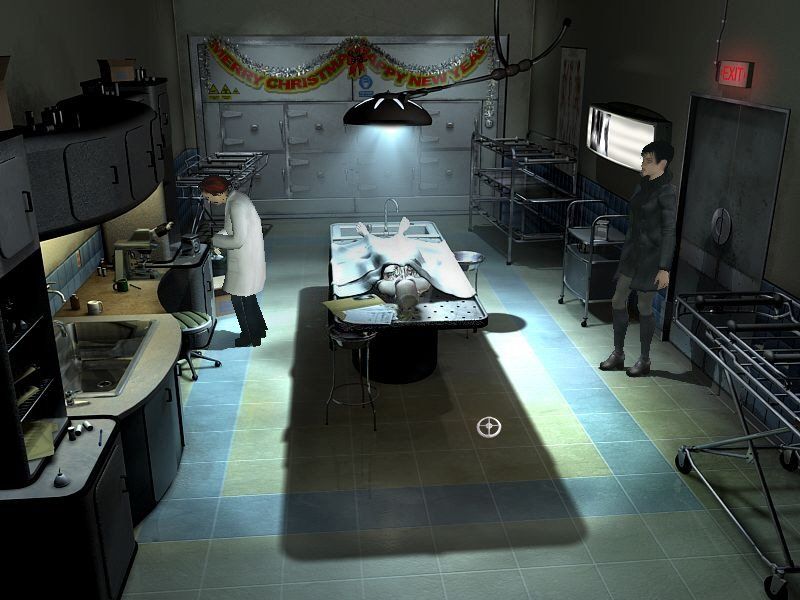

Thinking pragmatically, this style of game is also one that would be a lot simpler to implement than trying for anything action-oriented. It wouldn't require weeks of tweaking the physics to feel just right, nor will it feel empty without multiplayer, or require complex AI or something like that. Also, I have a story that's been burning a hole in my head and I think the best way to tell it is via a style of interactive fiction I adore. Making it 3D is also partially as a challenge to myself, but also as an homage to classic games like Still Life and Grim Fandango.

Unlike those classics I will forego the static pre-rendered background and go full 3D. Computers are nowadays by far powerful enough to render the necessarily complex scenes you'd need for an adventure game.

What would such a game contain?

- A character you control using the mouse (or tank controls if you're a brave soul)

- Varying locations to move between

- Objects to interact with

- Characters to speak to

- Items to pick up and combine with other things to solve puzzles

- Goats?

In terms of gameplay features it's not really that big of a list, but even these limited requirements betray the hidden complexity of building a system to support them all. Also a fully-fledged game product includes a myriad of hidden features that come as standard: the game needs to be aware of its state (solved puzzles, characters met, etc.), would need to save and load that state, support options to handle different hardware or user preferences, have sound and music, etc. There are dozens of other small details that I will remember only once I realise they're missing.

Despite the surface level simplicity this is a substantial undertaking and there is a high likelihood that it will never be finished or released in any capacity. Then again, this is not about making a marketable product as much as it's about giving me something fun to play with when I'm not writing terrible songs or getting destroyed in the pit.

As much as I have a desperate drive to get started with my actual dream project, I think for the sake of not spending the better part of the next decade on this experiment I am going to simplify the requirements that my game demo needs to fulfil. My aim is to have an animated character walking around in a simple room containing some things to interact with that just pop up a text dialog. This seems like a limited enough scope to be doable in a few weekends, but also will force me to solve some actual problems and get to know the tool so that I can make an informed decision. I'm specifically trying to get a feel for the following:

- Loading models and animations

- Rendering the models with dynamic lighting

- Implementing mouse movement

- Changing the camera when transitioning between spaces

- UI/text rendering

- Basic audio

I got a plan so let's get to it!

Getting to It

I've spent more weeks than I'd like to admit getting this done (I started this in June!!), but I was able to successfully make the game demo using both raylib and Godot. The actual finished products are messy and not worth showing off, but I've collected my thoughts on the different engines and have been able to come to a satisfying conclusion.

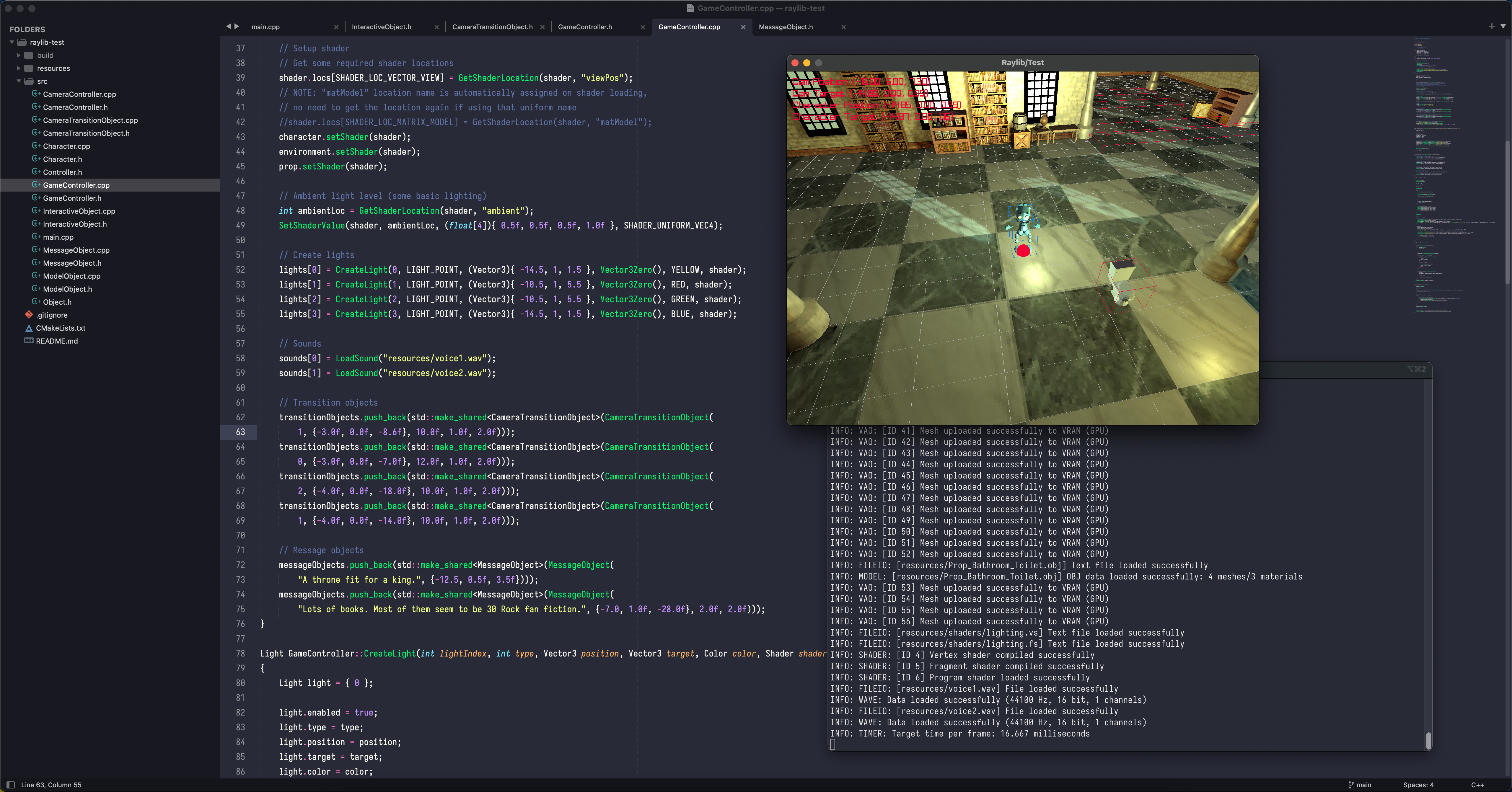

raylib

raylib claims to be "a simple and easy-to-use library to enjoy videogames programming." It was created by Ray Santamaria—whom the library is named for—and has gotten a fair bit of attention due to its ease of use and crazy amounts of bindings. It's essentially just a C library so it's easy to create bindings for every language under the sun. There is also a port for the SEGA Dreamcast, which I absolutely love ♥

I was attracted to raylib due to its popularity within the handmade games space and because I wanted to stretch my C++ muscles, fearing that they've atrophied since I last changed jobs. It also claims to provide the means to "enjoy videogames programming", which is exactly the experience I am after. With raylib being as simple as it was, I skipped over my usual process of learning by completing tutorials and just started working on the game demo, referring to the documentation and plethora of examples as I went along.

Working with raylib definitely lived up to its tagline and I understood why it has such a positive reputation. The library is simple and easy-to-use and I did enjoy the programming experience. The API—detailed in the extensive cheatsheet—feels like a comprehensive toolkit, giving you just what you need to get going and build games. You create a window using InitWindow, load models with LoadModel, and play sounds with PlaySound. If you have a basic understanding of games development, raylib is incredibly easy to work with and doesn't require you to get used to a complex architecture or indecipherable abstractions. I was responsible for structuring my code myself and raylib was just there to help me do the complex things that didn't pertain to my specific project.

However, despite its ease of use, it does feel like a toolbox for experienced developers rather than somewhere a novice can get their first start. It will happily make the first circle for you, but then you have to draw the rest of the fucking game. Doing something as seemingly simple as adding lighting requires you to understand the concept of shaders, write and apply them to your model's materials, and know where to logically place calls to the BeginShaderMode() and EndShaderMode() functions within your render process. Also, it not coming with a prescribed way to structure your code was a freedom that I found both liberating and intimidating, and I ended up refactoring my tiny demo a bit too many times.

In the end I quite liked using raylib. It claims to be simple and straight-forward and is exactly that; giving you everything you need and nothing else. It's the kind of experience that would frustrate some people but leave others feeling free to wildly create as they see fit. My initial excitement was mixed with trepidation about whether it would be too difficult for me, but to my great joy I found it to be not difficult at all and it seems perfectly suited for small games and experiments.

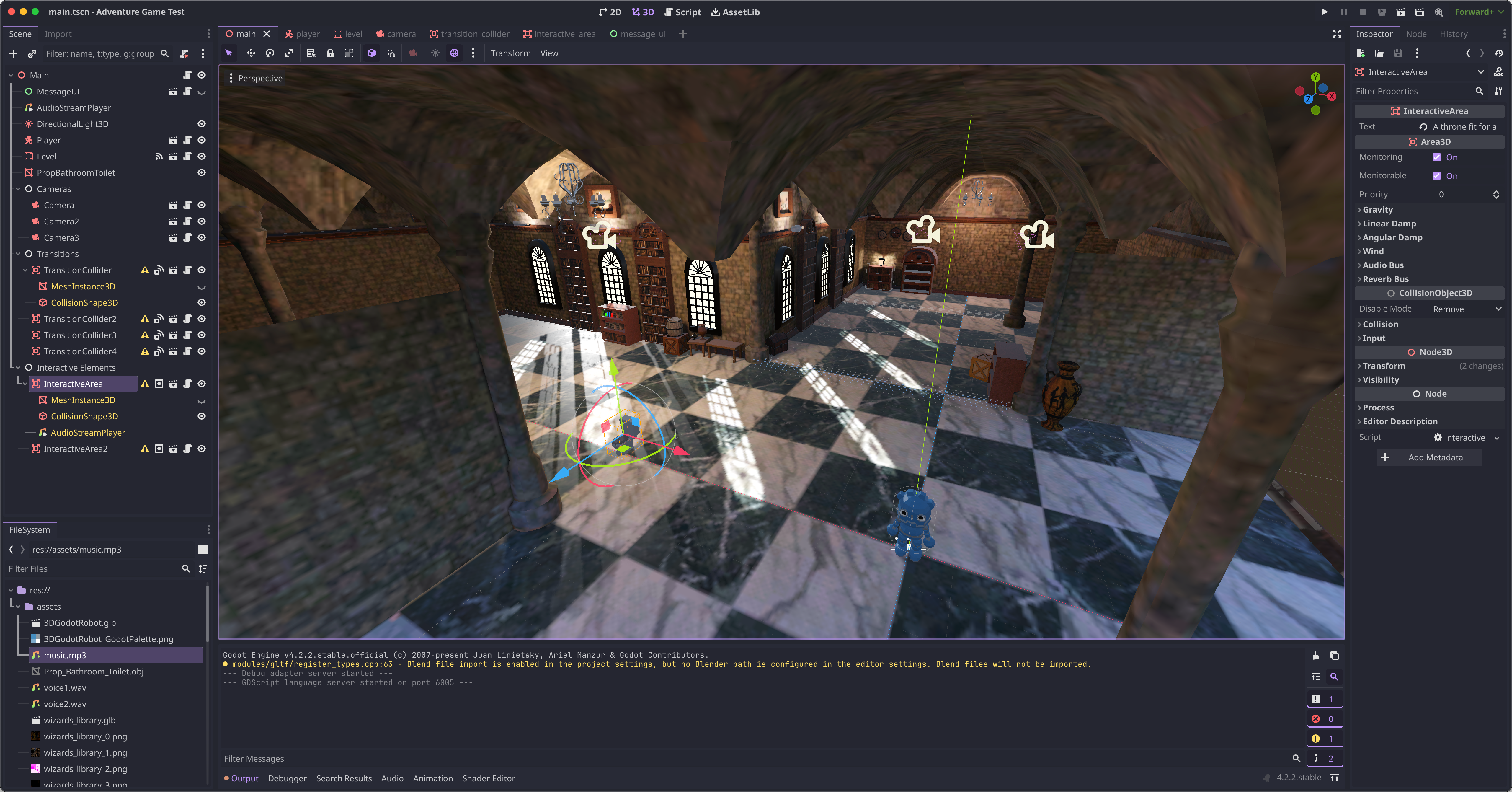

Godot

Godot is an open-source 3D game engine which has been under development for about two decades. It allows for building games using an interactive editor and its own scripting language GDScript, a language that has stolen all of its syntax from Python. Alternatively, you can use C# if you insist, and it also supports other languages through an extensions system. Godot recently gained a lot of popularity after Unity decided to burn the goodwill of its community, and the subsequent flurry of attention and work has pushed the engine to improve a lot.

I have some experience with Unity—not to mention having spent many an evening with UnrealEd as a youth—so much like how I wasn't digging into raylib as a complete novice I was fairly familiar with the editor-driven workflow. However, I was not prepared for how quickly and easily I got things working when I eventually sat down with Godot. I started by going through the tutorials in the official documentation and then, wanting more but not wanting to spend an inordinate amount of time learning, I worked through a bunch of the games in the Godot 4 Game Development Projects book by Chris Bradfield. That turned out to be a great resource as it build my familiarity and gave me several example projects to reference if I needed it.

In the end I was able to complete the rough game within a single day, much quicker than the two dozen or so hours I spent with raylib. However, I recognise that it isn't a fair point of comparison because the time I spent with raylib also included learning how to use it, whereas with Godot I learned the engine first before I started working on the actual game. And by virtue of using raylib first I had solved several gameplay problems with it which I then copied over to the Godot implementation, saving precious time spent on experimentation.

One aspect of Godot which initially intimidated me was how it's built on a hierarchical tree of nodes, all which come in different flavours with different uses and requirements. This requires a completely different approach than when dealing with Unity's game objects and components. However, once I understood the node structure and how some nodes interacted with their child nodes I didn't really have any trouble. The architecture has definitely grown on me and I now feel that seeing a tree of nodes makes it easier to quickly grasp how things are structured than having to scan a long list of complex components. I also noticed that I was spending more of my time in Godot writing code than tweaking component parameters in the UI like I would with Unity.

Final Thoughts and Feelings

I must say that working with the Godot editor was really nice. After having spent so much time doing things manually with raylib it was a breeze to put things together using a visual editor. What I gave up in direct control I gained in efficiency and it handled the random assets I had found for the demo much better than raylib. However, using Godot brought up some of the original trepidation that were the reason I wanted to run this experiment in the first place. Godot, Unity, and other heavy duty game engines are built on the idea that the foundation upon which your game is running is essentially a black box. You are provided with a lovely editor and lots of tools with which to build your game, but you don't need to know—nor are you necessarily invited to know—what's going on under the surface.

Not to say that raylib doesn't have its fair share of unknowns as well. I have only the vaguest idea how the graphics are rendered and I generally don't care as long as I can load a mesh and have it show up correctly on the screen. However, what I feel epitomises the difference is for example how a script in Godot can receive a call to _process(delta), which essentially functions as its main loop. You don't call it from a loop you yourself create, it gets called for you by some arcane process that dwells deep within the cyclopean halls of the engine's inner workings.

## Move the character to a given target position

func _process(dt: float) -> void:

var distance: float = position.distance_to(move_target)

if distance <= DISTANCE_THRESHOLD:

position = move_target

$GodotRobot/AnimationPlayer.play("Idle")

return

var travel_distance: float = move_speed * dt

position = lerp(position, move_target, travel_distance / distance)

look_at(move_target)

rotation_degrees.y -= 180 # the model is facing the wrong way :P

$GodotRobot/AnimationPlayer.play("Run")

There is nothing inherently wrong with this approach, nor do I really mind that there is a powerful engine running under the surface which I can tap into as needed. What I find uncomfortable is the seemingly uncharted depths of the engine and the implications it has on the code that I write. Godot is made up of nodes—a staggering amount of nodes—which you use to construct a hierarchy that defines your game scenes. They're all quite different and have different uses, and some of them need a specific child node or two to work correctly. There are also signals you can use to send messages between nodes, or you can always call methods on them directly if you have a reference to them, with nodes themselves retrieved by their names or based on which group they're in.

This inherent complexity is incredibly daunting to me as a novice and I have experienced it as a barrier to progress in the past. It's not necessarily that I don't know, or can't learn, how to accomplish something in Godot. The issue is that the overwhelming amount of choice means that I don't know what I don't know. The whole time I'm working on the game I have a sneaking suspicion that I'm doing something wrong. That my architecture is too convoluted, that I'm introducing needless inefficiencies, or that I'm not using the correct node for this exact scenario.

This type of insecurity isn't necessarily unique to Godot as I remember it from my time with Unity. There was always a feeling that what I was making can be done better somehow, but that I was completely unable to see it. In contrast, raylib's relative simplicity meant that I understood more of what was going on and I was more responsible for what was going on. I had more insight into where improvements could be made. With raylib I was much less likely to code myself into a corner because I was simply unaware of a key component or missing a fundamental understanding of how the engine wanted me to use it.

Perhaps the doubt will fade with time, as it has done in other avenues of my life, but the intent behind this experiment was to figure out how to enjoy game development. And if my enjoyment is the key metric, these kinds of doubts and discomforts carry a lot of weigh.

On Not Using an Engine

The distinction between what makes an engine vs. a framework vs. a library is a taxonomological discussion that is beyond the scope of this article. Godot refers to itself as a game engine and raylib refers to itself as a library, so I will defer to their self-prescribed labels and use my recent experience with both to philosophise a bit on doing engine-less development.

The advantages of using an existing game engine are numerous and seemingly intuitive. Most of the work is done for you and you can spend your time focusing on the gameplay and assets that make your game unique rather than worrying about the minutiae involved in getting the game to run. A common adage in game development circles is that if you want to focus on actually making a game you should use an existing game engine. Building your own, even using robust libraries like raylib, is going to demand so much of you and you will spend the majority of your time getting the fundamentals right rather than making the game enjoyable. If someone else was in my position I would most likely recommend using an established engine, especially for someone new to game development.

However, you are also completely restrained within the confines of what the engine is capable of and at the mercy of the architectural decisions of the engine's creators. If you attempt to stray outside of the boundaries of its capabilities you may either find it impossible, or must devote yourself to the gargantuan task of getting the engine to do something it wasn't made for. If the engine is built to be versatile enough to handle a myriad of different styles and genres, it will also be ladened with a dramatically increased complexity. This complexity may result in the engine working inefficiently and its black box nature means that you probably have no means to cut out the pieces you don't need. Nor would you even understand what it's doing or where improvements could be made. You may end up with a large unused chunk of the engine stuck to the side of your game like a vestigial appendage.

This is all very negative towards engines, but it's important to consider what you're losing when making a decision to use something that will do so much work for you. The decision will be weighted by what you want to accomplish and what you are interested in working on.

In contrast, with no engine to do the heavy lifting you will need to consider so many aspects of the development that you wouldn't otherwise. How do you organise your code? Do you go hard-in on OOP or try some sort of Frankenstein entity/component system? Do you create representative game objects? What about objects that have meshes but no physics object or vice versa? How can you communicate between them? How is meta-data about the objects stored? How much functionality and data lives in the global scope? How do you control animations? How do you activate/deactivate components/objects/whatever as they are needed? When do you allocate memory and how do you make it safe to despawn something? And then on top of all of this, how can you make running around in the game world feel good?

So many of these questions are answered for you when using an established engine. Engines force you to strictly stay within the lines, but as long as you do you can spare yourself the toil of having to figure out all this madness for yourself.

Conclusion

My philosophical musings on whether or not to use an engine aren't exactly novel nor particularly insightful. So have I wasted my time spending dozens of hours over a series of weeks running this experiment? I would say no, as building the same demo using both Godot and raylib allowed me to feel the distinction between the two approaches in a way that I didn't before. I became very aware of the staggering amount of work that using a library expected of me, and when I switched to the engine I felt liberated from that, only to feel almost trapped by its conventions.

In the end this experiment was for my own sake, to get a feel for what I would prefer. When I dig a hole do I want to be handed a simple shovel, or do I want to sit in an excavator with a thick manual on my lap? I'm glad that I was able to overcome the trepidation I felt towards digging into Godot, and I was equally enthralled by the promise of raylib's simple design. This article was an indulgence of my curiosity and isn't here to serve as an objective comparison of either approach, but I would wholeheartedly recommend both Godot and raylib to anyone looking to make games.

Having concluded this little endeavour and considered my options, I must admit that there is a, perhaps naïve, romance in the idea of building my own engine. Of going back to my roots and using a slew of libraries that I patch together in an ever-evolving project that is a reflection of my interests and my abilities. To be master of my domain and gain deep knowledge of algorithms, architecture, and efficient design. Building only exactly what I need and crafting a sleek, minimalistic expression of my dedication and skill as an experienced programmer!

Or I could just use Godot and finish the game within the next decade.