An Amateur's Guide to Mixing Live Music

Inspired by the relatively successful show I put on a few months ago I reached out to a friend who used to do concert booking about maybe working together. She had been considering getting back into the game as she had contact with a venue, but was missing a sound engineer and for the size of the shows she was putting on she couldn't afford to hire one. Well, I had done some mixing for bands that came to visit the office when I worked at TIDAL, so I thought maybe I could do it?

I mean, how hard could it be?

I've now successfully mixed four shows for Nosegrind Events and I can tell you that at the scale we're working with it's actually surprisingly straightforward. The first time I did it I was working with a such a high level of stress for the entire evening that I had to lie down on the floor multiple times. But my many years of experience being in a band had taught me 80% of what I needed to know, and the other 80% comes down to planning and quick improvisation. So for the sake of collecting my thoughts, and to potentially pass on knowledge to anyone who may want to give it a try, I'm going to document what the experience is like.

The Equipment

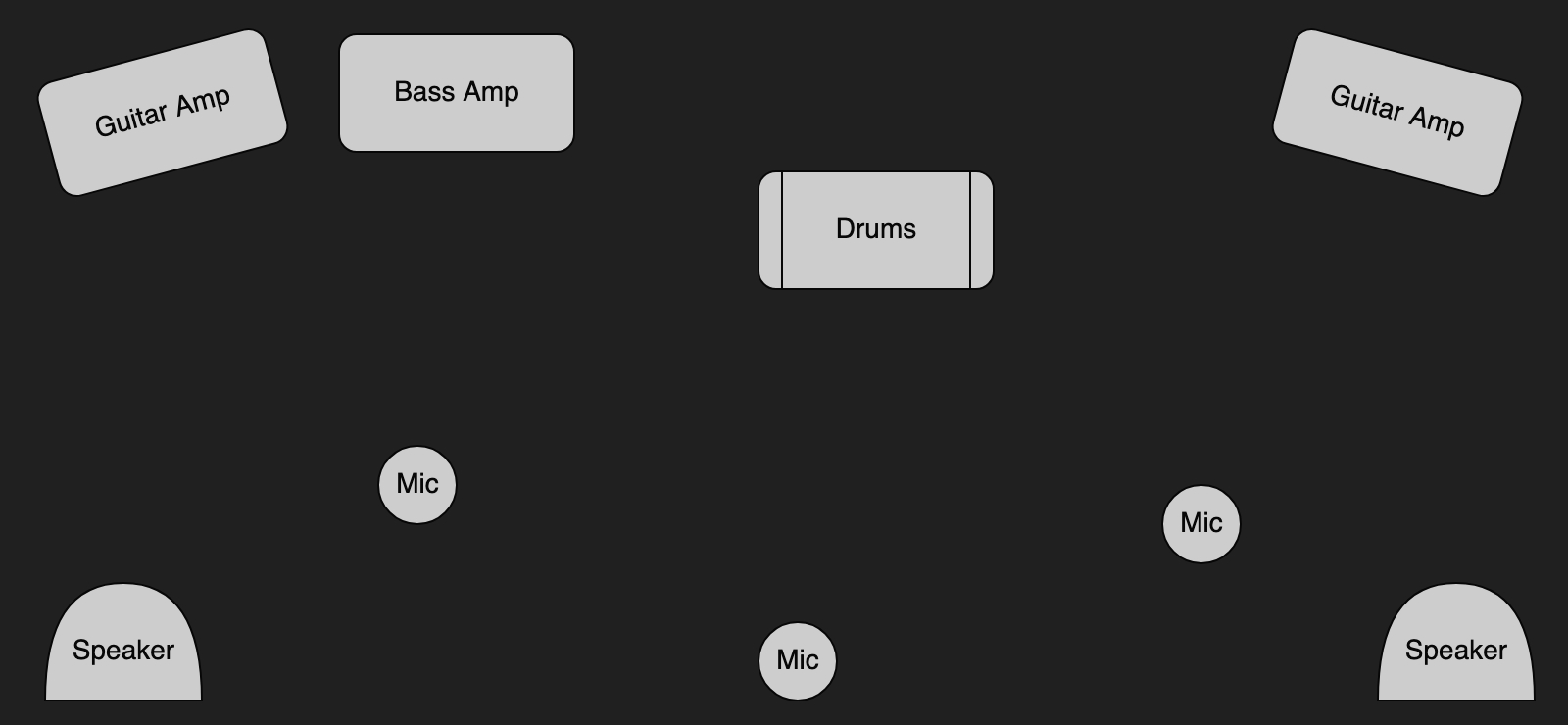

For the type of show and the size of the venue, the equipment is very minimal and quite typical. We're talking about the classic "rock band" setup with a drum kit, a bass amp, one or two guitar amps, and up to three vocal microphones. Lots of bands have a backing track as well, some may bring other instruments, and some would want to plug their instruments into the PA instead of an amp. But in general it's all just variations of the same theme which thankfully makes things predictable. Also, the fact that it's a tiny venue means that we don't bother to mic up the amps or the drums. This reduces the amount of inputs I need to worry about going into the dinky little analogue 8-channel mixer I' have to work'm working with.

Because the room is so small we can also get away without needing a stage box of any kind, just running everything through an XLR snake (basically 12 XLR cables in one bundle). That way the mixer can be on one side of the room directly across from the "stage" and I don't have to worry about how we're running a series of cables across the floor. Aside from the amps, microphones, and instruments we have a pair of speakers that are blasting out everything coming from the mixer.

I know that big professional productions are a lot more complicated that this so I don't want to dismiss the invaluable work real sound engineers do. I just want to illustrate that if what you want is to put on a show with a band you don't need a lot more than the things that make the noise and a way to make the vocals audible over it.

Planning Appropriately

Like I mentioned in the start the bulk of the work is in being prepared and dealing with unforeseen eventualities. To that end, here is what I bring to every show:

- A set of power strips (the venue never has enough)

- A whole bunch of XLR cables of varying lengths (the venue never has enough)

- A few extra instrument cables (the bands usually don't have enough)

- Extra microphone (you never know)

- Several DI boxes

- Scissors

- Cable ties

- Cable snipper

- Drum key

- Multi-tool with screwdriver

- Duct-, electrical-, and masking tape

- Markers

- Notebook and pen

- USB charger and cables for lightning, mini USB, and USB-C

- Pain killers and adhesive medical strips

A lot of these things are things that I already had the habit of bringing to shows that I was playing, usually as a result of needing them at one time or another. I know that it's not necessarily my responsibility to take care of everything—I am in theory just responsible for the sound—but if something needs to be fixed the bands tend to ask the sound engineer first, so I want to be sure that I'm a useful resource in those cases.

Another important aspect of being prepared is to know what the bands are bringing beforehand, meaning I need tech specs. These are documents which detail what instruments and equipment the bands are bringing and potentially what they will need from the venue. There is no standard format and I have received everything from two sentences in a Word document to a multi-page PDF, but I always end up copying them into a page in my notebook and use that when I'm rigging up to figure out what we need and what gets plugged where. I also like to put some masking tape on the mixer and mark up what the inputs are so I don't forget.

Bands are generally good at putting what they have and what they need on their rider, but there are always some unforeseen changes so I've learned to think on my feet. Being so fastidious about planning beforehand isn't just about reducing my stress leading up to the show, but to remove as many unknowns as possible to make room for other unexpected eventualities.

Basics of Mixing

Alright, so at this point we have all the equipment on stage, the band has set up and are ready to go, and everything that is going to the mixer has been plugged in. What do you then do with it all?

Instruments, including the human voice, need to be mixed relative to each other in volume and they all have different frequencies where they sound their best, so my job is to... do that. Now I can't speak for any other venues than the ones I've worked at but for me the name of the game is just to make everything audible over the drums. In a small room a traditional drum kit is crazy loud and the main reason why everything needs to be pushed to an ear-destroying volume¹. This means that there is nothing really to be done about "balancing" the sound, or "carving out" neat gaps in frequencies to make room for other instruments. Just crank it all to 11 and hope nothing breaks while the drummer beats the everliving hell out of the drum kit.

Having instruments plugged into their respective amplifiers makes this a lot simpler, as the amps have different characteristics and sit in the frequency space associated with their instrument. It also helps that they are separate sound sources from the PA and are placed in different locations so you can really push their volume without them necessarily drowning each other out. A loud bass amp will be heard under a loud guitar amp just because they make different types of sounds and our ears are good at filtering for different frequencies when we pay attention.

So with the drums set to it's (only) volume and the amps pushed to what they need to so as to be heard over the drums, we then focus on the mixer itself.

The Signal Chain

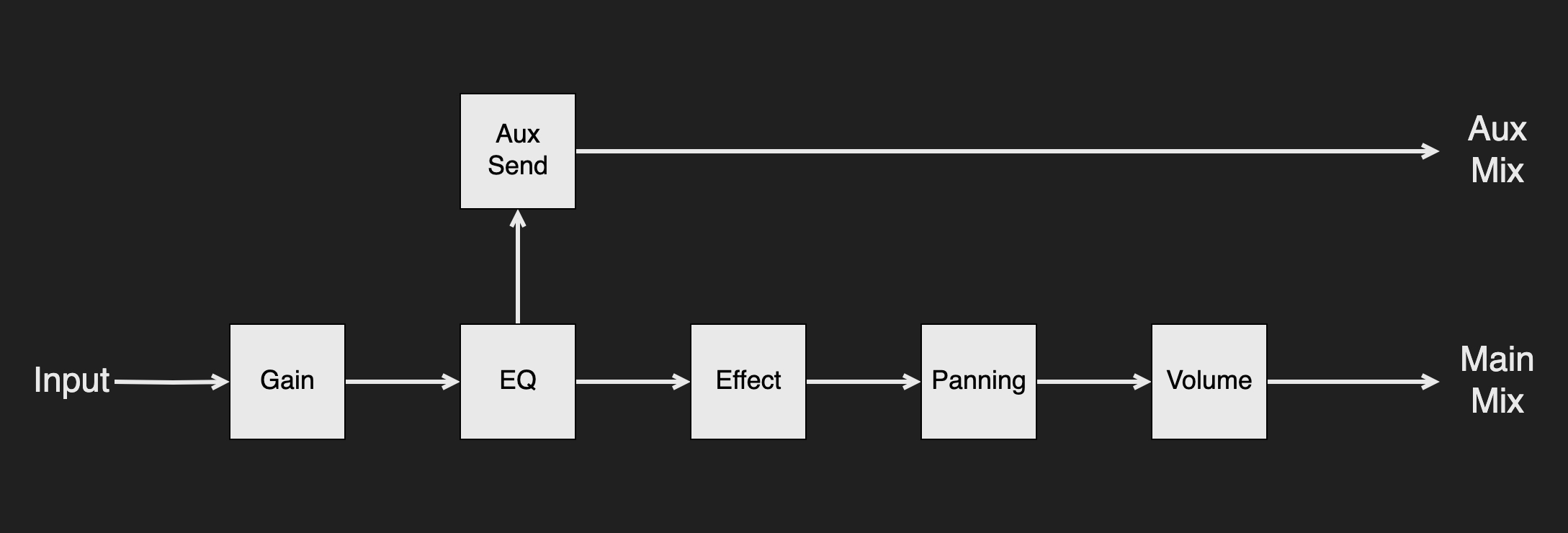

The signal comes from the instrument/microphone and goes in to the input, then through the following stages on its way to the main output:

- Gain - Boost the intensity of the signal.

- Equalisation (EQ) - Adjust (boost/attenuate) the intensity of the signal for different frequencies.

- Auxiliary Send (AUX) - Send the signal to a separate auxiliary mix bus; used to give performers a separate mix in their monitors.

- Effects (FX) Send - Send the signal to a separate effects bus where the effects are applied.

- Panning - Pan the signal to the left or right side of the mix.

- Volume fader - Adjust the volume of the final signal in the main output.

This is a linear signal chain, which means that things that are done earlier in the chain affects the later stages, but not vice versa. You can on some mixers, toggle whether you want to send the signal to the Aux bus after it's passed through the whole chain, but I've never experienced anyone wanting that. The Aux mix is usually the one that the performers hear on stage, referred to as their "monitor mix" (as it's going to floor monitors or individual in-ear monitors).

Gain Staging

As one of the most important jobs of an audio engineer is to balance the volume of the different instruments, then you need fine grained control over their respective volumes. With an as rudimentary setup as we are working with it isn't always possible to have this control, but I have no shame and will run up on stage to twist the volume knob on an amp in the middle of a set if need be. I always warn the band beforehand that this may happen and nobody has yet to tell me off.

But to gain this kind of control of the signals coming in through the mixer you need to do something called Gain Staging². Gain Staging is a somewhat complex concept that has to do with balancing the noise-to-signal ratio as well as ensuring you're feeding the EQ/effects the best possible signal. In practice it just means that you need to make it as loud as you can as early as you can.

If a signal is too loud for the output it can result in clipping, which is a topic that is too large and complex to get into here, but the effect is one you should be familiar with: if it's too loud it will sound distorted. So to avoid this we need to thread the needle between getting as loud of a signal in as possible and not having it be too loud for the output.

Ideally this is handled on the instrument side, with them sending the signal as loud as they can because the earlier things are boosted the less likely it will introduce noise coming from the equipment or the cables. However, we don't want it coming in too loud (or "too hot") or it may overload the speakers without us being able to turn it down. So to find the balance we use the Gain know on the mixer. Turning it up, means that the signal is boosted (louder) and turning it down means the signal is attenuated (quieter).

You generally want the highest peaks in the signal to be at 0db to ensure it's not clipping and some mixers, including the one I'm using, have a feature called Pre-Fader Level (PFL) which allows you to see on the meter (the thing on the side with the red/yellow/green LEDs) how loud the signal is coming through during the gain stage. So we push the instrument as loud as it will go, for example asking the vocalist to make a loud sound, and then adjusting the gain so that the signal stays as far up in green zone as it can be without going any further.

To me this is the most important part of a sound check that a band does before performing. I will mess with the faders a lot during a performance in response to the changes in the music, but it's so important to get the initial signal intensity set correctly as it affects everything further along the chain. So if all we have time for is what is called a "line check" we just go through all the instruments and make sure that the gain is set correctly so each signal is coming in as loud as possible, but no louder.

EQ Tips

So now that you have the signal coming in nice and loud you need to EQ it so it sits nicely in the mix with the other instruments. This is an art that I consider to be indecipherable black magic and I don't know anything about how to do it well.

That being said, the small-scale shows that we put on it don't really require a lot of knowledge to get it vaguely right. EQing for live shows is more about carving out space in instruments that don't need those frequencies than it is boosting where it is needed. The fact that I'm working with an analogue mixer that only has three knobs for adjusting EQ also means that there isn't much I can do.

So here are a few things that I have learned and that I basically do for every show:

- Vocals don't need low frequencies and in small reflective rooms microphones have a tendency to pick up and feedback those frequencies. So if you can, run it through a low-pass filter (which are customarily at around 80Hz), or just cut the signal on whatever low frequency you have control over.

- Incidentally, vocals could use a boost in the high-mid frequencies to cut through other instruments. If you push it too much then vocals can get annoyingly harsh, but around 3-4kHz is the range where vocals is best heard so they will often need a little help there.

- Bass guitar, despite it's name, can get a bit boomy on the really low end so I will cut those frequencies if there seems to be a bit of ugly noises coming from there and instead boost a little bit on the low-mid range. This isn't as much of a problem if the bass is being played through an amp instead of the mixer, as the amps tend to be adjusted to give bass it's "weight" without it sounding bad.

- Heavily distorted guitars, the bread and butter of the bands we put on, lose a lot of mid-range when going through all those harsh effects. It can result in a very top-heavy signal and I sometimes will cut the high frequencies and boost the mids to compensate. Don't go overboard here as it may drown out the vocals.

- Bands who have a backing track tend to put electronic drums, samples, and things like bass drops on the track. So I generally always boost the low end to make sure any sub-bass effects are felt by the crowd.

Keep in mind that these are all based on my limited experience and shouldn't be hard rules that you have to follow. I could be very wrong in my assumptions about how things should sound, but by not having any formal training and only working in a small room with limited resources, I haven't really been able to learn the right way. Use at your own risk!

Monitor Mixes

The Aux Sends determines how much of each signal to send to the Aux mix bus, essentially just another mix that can be sent to floor monitors or in-ear monitors for the artists. These work essentially as a fader for the aux mix and what you reach for when the vocalist says "can you turn me up in my ear".

I have not had the pleasure of doing a separate monitor mix at our shows, pretty much because we don't have floor monitors, but I've done it at rehearsal for my band. It's just a matter of letting the vocalist setup his in-ear monitors, making sure the signals are gain staged correctly (see above), and then listening to his instructions on what to turn up or down.

Adding Effects

Finally, before the fader you get the opportunity to send the signal, having passed through the gain and EQ stages, to a separate FX bus. The FX bus functions as its own separate channel where the combined sound of all the signals that have been sent to it has effects applied to it and which can then be sent to the main mixer.

Customarily I've only ever added some reverb or a slap-back delay to the vocals, so it's helpful to be able to send only some channels to the FX bus. Often this comes with its own fader which controls how much of this separate channel signal is sent to the main mixer.

During the Show

Alright, so we've sound checked the band and opened the doors, the audience has arrived and the time has come for the show. We do a final signal check, lower the volume on the background music, and they start the performance.

Now what?

Three words: Push. The. Vocals.

As I mentioned earlier, a sound engineer's most important job is to balance the volume of all the instruments, but if we're being honest with ourselves the mostest important job is to make sure the vocals can be heard over the din of distorted guitars and beaten drums. I keep an eye on the main meter to try to ensure we're not pushing into the red and potentially damaging the speakers or distorting the sound, but I will push the volume as much as is needed to make sure the vocals are heard.

In the kind of room I'm working in, which is small and cramped, and where the drums dominate the soundscape, we have to do what we can to make the songs sound as good as possible. If I have control over the guitar and bass I will try to give them more volume—essentially more focus—when it's their time to shine, during a solo or a tasty riff for example, but for the kind of contemporary popular music that we play people pay most attention to the vocals so they need to be heard above everything else.

Sometimes a guitar player will turn on an effect that is much louder or a vocalist will sing softer or the drummer is taking out their aggression on the kit, and I will need to adjust the faders to compensate. I sometimes turn on PFL for a channel and play with the gain, or adjust the EQ a bit in response to feedback or to give it more space to be audible, but in essence I'm just juggling the faders to make sure the band sounds as good as possible no matter what they're playing.

Putting in more work before the show, both in the days leading up and on the sound check, makes this part a lot simpler. Sometimes I can even lean back and actually enjoy the show.

Afterwards

After the show is done and all the bands have played their sets it's time to pack up the equipment. This is my least favourite part of the experience and it's annoying how it comes at the end, after I've been hyper focused for many hours and just want to go home and collapse on the couch. But it's important because the work done now will make it easier for me the next time we put on a show.

All cables are wrapped correctly and held together with velcro strips; different cables are kept in different containers; drums are dismantled and put into bags; amplifiers and speakers are stacked into the corner. The money spent on containers and strips and things to help you keep things organised save so much time in the long run, and the clean up job sucks but is worth doing well.

Then after I've had a final drink and collected myself along with my things I head home, tired but satisfied. I absolutely love live shows and I'm happy to be able to make them possible, both for the bands and the fans that come to see them.

¹ Always wear earplugs when you're at a concert 💜

² If you're an actual sound engineer please don't be mad at me for simplifying/butchering this concept.